Native Son – August, 2011

Juniper-covered cliffs overlook the bone-dry Paluxy River. All photos by Steven Chamblee.

Native Junipers: Road Trip to Glen Rose

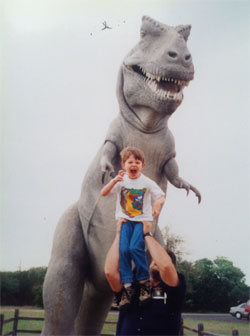

Ferocious beasts at Dinosaur Valley State Park in 1999.

Boy, oh boy, you know it’s hot and dry outside when you go to hang a load of laundry out on the line and by the time you’ve got that last wet shirt hung up, you can just go back to the first one and start takin’ ‘em down. I try to be an optimist, so I figured there must be some kind of upside to this summer … and I found one. A friend of mine alerts me that the Paluxy River down by Glen Rose is so dry that there are more riverbed dinosaur tracks exposed now than any time since the 1930s. Good enough for me, so I tell my 18-year-old son about it. He was a huge dinosaur fanatic when he was little, and I remember well taking him down to see the tracks when he was about six years old. Three shrugs, two grunts, and one dramatic heavy sigh later, he’s game to go.

Let’s face it … this is not a pretty summer for Texas road trips, but this is still the Lone Star State, and beauty is still where you find it. The pastures and bar ditches along the way are burnt to a lovely sandpaper hue (let’s call it “tawny”), and many of the broadleaf trees are gasping and wheezing like a fat guy hiking in Colorado (“hey … I resemble that remark!”), but the native junipers are a robust dark green. In startling contrast to the dry, parched hills, they look like giant heads of fresh broccoli hot-glued to a haystack. You’d think folks would appreciate their winsomeness, particularly during this blast furnace summer, but alas, this is not always the case.

Ashe juniper forms a low, rounded, dense canopy.

Some folks call them “cedars,” but they’re not cedars. Botanically, cedars (Cedrus spp.) are Old World plants, with four species native to western Himalaya and the Mediterranean. Some folks call these familiar trees “invasive cedars,” but they’re not introduced plants. These are native junipers (Juniperus spp.), and there are at least nine different native species in Texas. A whole lot of folks call them “@%$$#@ cedars,” because they tend to overgrow pasture land … with a vengeance. That’s true enough. If you are a rancher, you need healthy stands of forage grasses, and these junipers can quickly colonize and shade the grasses out. Historically, fire used to keep their populations in check, but since we keep putting out the wildfires, we also defeat nature’s juniper suppression method. (Such is the price for permanent settlements.) Junipers have scaly leaves that contain a resinous sap that ignites easily and burns almost explosively during wildfires. This kills the trees and allows the grasses to re-establish rapidly into forage-rich prairie.

Typical single trunk habit of eastern redcedar.

Blue “berries” of eastern redcedar are actually fleshy cones.

Three of these juniper species’ native ranges overlap around Glen Rose and “introgressively hybridize” with one another (the biological equivalent of putting all of their distinct genes into a blender and hitting the “frappe” button), so sometimes it’s difficult to know for sure exactly what you are looking at. Eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) is the largest (to 50 feet) and most widespread of the three, ranging from South Dakota to Maine, southward to Georgia and westward to just a few miles west of Glen Rose. Oversimplistically, it usually has a single, straight trunk and produces clusters of blue fruits. Redberry juniper (J. pinchotti) ranges from northern Mexico to western Oklahoma, and eastward from the southwest tip of New Mexico to a few miles east of Glen Rose. It has a multi-trunked habit to about 20 feet, and has, of course, reddish fruits. Redberry also has the ability to re-sprout from root buds after a fire, so it is especially tenacious. Ashe juniper (J. ashei) looks a lot like the redberry juniper in its growth habit, but has blue fruits. (Technically, all of these pea-sized fruits are fleshy cones, but they look like round berries to most people.) Often called mountain cedar, ashe juniper is infamous for producing clouds of pollen that send many allergy sufferers into fits. Personally, I find it noteworthy to mention the plant’s particularly potent foliar “aroma,” which generally goes unnoticed outdoors … until someone tries to circumvent the $100 Christmas tree racket, harvest an ashe juniper from an unsuspecting rancher’s fence line, and bring it inside the house during the holiday season. Lord have mercy, it smelled like two male bobcats tried to lay claim the living room.

T-rex model from the 1964 World’s Fair.

A considerably calmer son visits his old friend in 2011.

So we finally get down to Dinosaur Valley State Park, pay the all-too-modest admission fee ($5), and roll on toward the famous footprints. Suddenly, giants loom ahead … I had almost forgotten the life-size dinosaurs on display. Salvaged from the 1964 World’s Fair exhibit in New York City, the Tyrannosaurus rex and Apatosaurus sent my then six-year-old son into a squealing celebration and roarfest back in 1999. He ran full speed in circles around them for a full 10 minutes, screaming and waving his arms about wildly the whole time. Today, he quietly studies the figures and gives me a rather eloquent explanation about how the vertical stance of the T-rex is incorrect, due to the artist’s antiquated understanding of the hip bone structure … but that’s what everybody thought back in those days. He acquiesces easily when I ask him for a photo with the toothy beast. I think he is remembering that childhood trip, too.

Sauropod and Carnosaur footprints tacitly speak volumes about the past.

Carnosaur footprint dwarfs Steven’s size-16 foot.

Down in the dry riverbed, the tracks tacitly testify to a world, a time, a story of amazing proportions. About 113 million years ago, almost 50 million years before T-rex came to be, a herd of 20-ton sauropods (plant eaters called Paluxysaurus) once traversed this ground, this exact spot. Their huge feet drove footprints deep into the mud on the shore of an ancient ocean. The young ones stayed within the circle of elders for protection from the carnosaurs (meat eaters named Acrocanthosaurus), proving the existence of social structures within the herds. Appearing with and among the sauropod tracks are the footprints of various sizes of the carnosaur … they had communities, too. Coincidental beachcombing, or evidence of a hunt? Were the tracks all made the same day, the same hour? Did the carnosaurs attack, or were they held at bay by the bull sauropods? Where did they go after they left here?

Can you spot the lizard?

By the time you read this, my son will be away at college. Will he study enough? Will he eat right? Will he learn when to be assertive and when to lay low? Will he meet a wonderful girl and fall in love? Will he ever want to see me again … except to ask for money?

Hmmm … seems like life on this earth has always been a mystery.

Peace & love,

Steven

Click here to find more information or call 254-897-4588.

About the author: Steven Chamblee is the chief horticulturist for Chandor Gardens in Weatherford and a regular contributor to Neil Sperry’s GARDENS magazine and e-gardens newsletter. Steven adds these notes:

Make sure your summer’s not a bummer. Head out to Chandor Gardens for a stroll in the shade. Just take I-20 west to exit 409, hang a right, go 2.1 miles and hang a left on Lee Avenue. Head straight 12 blocks and you’re driving in the gates. Call 817-361-1700 for more information. You can always go to www.chandorgardens.com for a picture tour and more information.

I can always use another road trip! Let me know if you’d like me to come out and speak to your group sometime. I’m low-maintenance, flexible, and you know I like to go just about anywhere. No city too big; no town to small. Just send me an e-mail at schamblee@weatherfordtx.gov and we’ll work something out.