Native Son: Two Cedars and a Well

Got a wild hair and headed south on 281 to Blanco, hung a hard left. I was headed to that little sweet spot in the Texas Hill Country called Wimberley, but I didn’t even make it half a mile down 163 when I had to slam on the brakes and turn around for a Cool Tree Emergency. I couldn’t believe it, but there it was…a big, beautiful cedar tree, about as rare in Texas as a polka-dotted armadillo.

Just to be clear, this wasn’t one of those native Texas “cedars” that are causing all that allergy misery this time of year…those are actually junipers. There are only four true cedar (Cedrus) species on the planet, and they’re all Old World plants. Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani), Atlas cedar (C. atlantica) and Cyprian cedar (C. brevifolia) are all native to the mountainous regions ringing the eastern half of the Mediterranean Sea. The fourth, Deodar cedar (C. deodara), is native from eastern Afghanistan to western Nepal.

The fantastic Deodar cedar in Blanco, with its cantilevered branches and four-sided needles. Click image for larger view.

Left: An Atlas cedar at Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania. Right: blue Atlas cedar at Chandor Gardens. Click image for larger view.

So I figure this particular Cedrus is either Deodar or cedar of Lebanon, simply because it doesn’t look like an Atlas or Cyprian. Deodars are much more common in Texas, but it really lacks the trademark nodding tips. I’m not sure cedar of Lebanon will even grow in Texas, but the needles look like that to me. Feeling needy, I get Greg Grant involved via phone and text. We hash it out a bit (oh, about 4 hours worth, including talk of old dogs, chickens, and the need for world peas) and decide it’s a slightly unusual-looking Deodar. Onward…

Wimberley, Texas, is a lovable little place. One minute you feel lost in the woods, the next you’re doing your best to hold onto your wallet while immersed in quaint touristy shopping. A few bags of goodies later, you’re back in sweet Mother Nature’s arms.

The charms of Cypress Creek are undeniable. Bald cypress trees line many Hill Country waterways. Click image for larger view.

Left: Giant cowboy boot painted with Texas native plants. Right: Shopping under the stunning live oaks. Click image for larger view.

I finally made it to Jacob’s Well, a quirky little spring that emerges right from the bed of Cypress Creek. Now I’ve seen plenty of photos of this sweet swimmin’ hole, but truth be told, I believe they were all taken with a wide angle lens, because it’s quite a bit smaller than I anticipated. Even so, it’s much larger than its biblical namesake and something you should see. The hole itself seems only about 10-12 feet wide and opens up like a bugle near the top. It appears to be 30-35 feet deep, but actually branches off into a cave system that is at least 140 feet deep. I’ve heard the water’s quite cold (68°F), even in summer. If it wasn’t January, I don’t think I could have resisted a quick plunge, if only just to ward off middle age for a few minutes.

Steps help, it’s still a tight squeeze to get through the clefted boulder and down to water’s edge.

What you rarely see in the Jacob’s Well publicity photos are the uber-cool, contoured limestone walls along the north side of the creek and the beautiful native plants tucked in among the live oaks, cedar elms, and those ubiquitous Ashe junipers. They met me like old friends as I walk along the trail…agarita, evergreen sumac, white mistflower…even the ball moss gave me a smile.

Water-smoothed limestone boulders and evergreen sumac keep you company at Jacob’s Well. Click image for larger view.

Ball moss and lichens on a pollen-loaded male Ashe juniper; Fleshy cones adorn a nearby female.

On my way out, I stop to visit the Jacob’s Well Cemetery. Personally, I don’t find cemeteries sad or the least bit creepy. I view them as a place to reverently learn about and pay homage to those who have gone before us in this life. Today is no different. I learn that the settlement here was founded in 1876, and the cemetery in 1883. Two Texas Rangers (the lawmen, not the ball players) are buried here, as well as Civil War veterans.

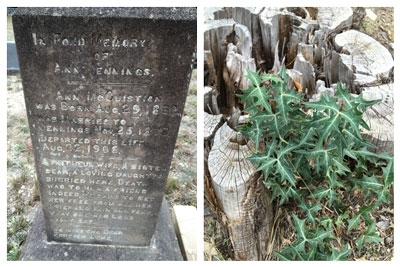

Life certainly has its balance of life and death. One tombstone declares that death was a friend to a suffering woman. Nearby, a tiny agarita literally springs forth from a dead juniper stump, a tacit reminder of our limited time on Earth and that life indeed does go on. Yes, it does, folks…we best make the most of it.

Left: Jacob’s Well Cemetery. Right: Tiny agarita springs forth from a dead juniper stump.

_________________________________________________

Your Lagniappe

While I was researching the Phoenicians (don’t ask why I do these things), I discovered something I find amazing.

Boustrophedon — An ancient bi-directional technique of writing lines of text turning at the end of a line like an ox at the end of the row. Compare it to our modern system.

(→) For example, a left-to-right text would appear like this

(→) and continue on the line below from left to right.

(→) Then it would start again and go like this. It does

(→) not require you to learn to read backward. Thank goodness!

(→) For example, a boustrophedon text would appear like this (↓)

.tfel ot thgir morf woleb enil eht no eunitnoc dna (←)

(→) Then it would start again and go like this. It does

!drah s’thaT .drawkcab daer ot uoy eriuqer deedni (←)