B.R.I.T. reaches a milestone

My dad and my uncle were both PhD botanists from the University of Nebraska. Somehow, they both made their ways to the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas, now better known as Texas A&M University.

Uncle John taught Plant Taxonomy (the science of identifying and classifying plants). My dad Omer branched off into Range Management, partly I’m sure because of the 17 years he spent prior to A&M heading the Biology Department at Sul Ross State Teachers College in Alpine in the Big Bend Country of Brewster County where ranching reigns king.

These guys never went anywhere without a plant press in their car trunks. I had my own press as well. (Didn’t everybody?) And, as a kid I spent countless hours over in the A&M herbarium as my dad chatted with curator Frank Gould (another botanist) discussing obovate leaves and peduncles on flowers. The Gould kids, Uncle John’s kids and I grew up together. It’s amazing we don’t all speak Latin.

When SMU needed to close down its herbarium they were looking for a partner to assume the collection. Eventually it made its way to a warehouse in Downtown Fort Worth and from there to the grounds of the Fort Worth Botanic Garden, a logical partner.

The news release I received a few days ago said that this entry of Rhododon ciliatus, commonly known as Texas sandmint, had just become specimen number 1,500,000 for BRIT.

“It’s an exciting milestone for the institution,” says Herbarium Director Tiana Rehman. “This achievement represents thousands of people studying plants over hundreds of years.”

I’ll let you read directly from the news release:

The role of herbaria in botany and conservation

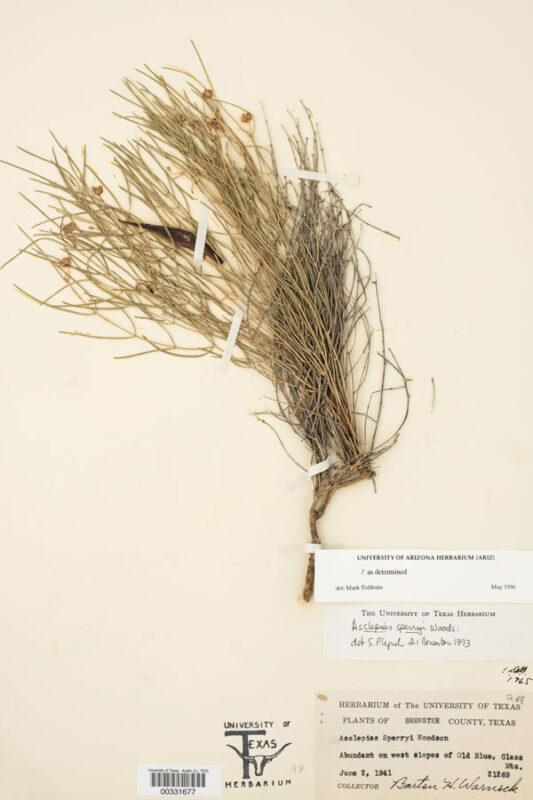

Herbaria have been essential to the study of botany since at least the 1500s, and the fundamentals have changed little since then: scientists collect plants, dry and flatten the specimens, mount them to cardstock, and label the specimens with information such as the names of the plants and when and where they were collected.

The biggest change from the 16th Century to today is that now specimens are photographed and their related information added to sophisticated databases with online access. These databases are structured so that their information can be analyzed for insights by scientists in many disciplines.

“Digital herbaria are fantastic, because they allow scientists anywhere to study our collection,” says Rehman. “But the actual, physical specimens remain essential. They represent a primary source of information that can be studied in many ways.”

Each specimen is a snapshot of a plant growing at a certain place and time. “That makes every specimen irreplaceable, because you can never recreate the moment when that plant was collected,” says Rehman.

A little about this particular plant…

You can get a feeling for the importance of a herbarium when you read the biography of the Texas sandmint.

Back to the news release:

Rhododon ciliatus, a ghost coastline, and the importance of plant conservation in Texas

BRIT’s 1.5 millionth specimen was collected as part of the Texas Plant Conservation Program, which is dedicated to safeguarding native plant species and restoring habitats.

Rhododon ciliatus grows in a particularly threatened ecosystem known as the xeric sandylands. This is a narrow band of sandy soils, no more than 12 miles wide but 400 miles long and up to 3000 feet thick, that stretches along a gentle curve roughly parallel to I-35 from Canton in Northeast Texas to the border of Bexar and Atascosa counties south of San Antonio.

The soils in this ecoregion were deposited during the Lower Eocene, roughly 56 to 48 million years ago. During this period, sea levels were generally higher than today. The sandy soils are the remains of this lost coastline.

When the sea receded, a unique ecosystem adapted to this habitat, but the ecosystem is at risk due to cultivation, urbanization and land fragmentation. As a result, several plants that grow only in this habitat are now at risk of extinction.

“The BRIT Herbarium contains many plants like Rhododon ciliatus, plants unique to one place in the world,” says Rehman. “Some we know about, but others might be hiding in the herbarium because they look like a closely related species. That’s another wonderful thing about herbaria—they hold undiscovered treasures!”